Wired for Innovation? Not by Accident

Jen Hetzel Silbert, Co-founding Partner

@jhsilbert

Welcomed or not, change is difficult and uncomfortable—painful even. The human brain is programmed to make this so. Likewise is it programmed for re-wiring when the right stimulus comes along, like a shift in conversation from telling to asking. May seem trivial, “ask don’t tell,” and yet it can be the key to unlocking breakthrough thinking – not just as a spontaneous spark, but more like an enduring flame, making innovation a cultural norm.

Welcomed or not, change is difficult and uncomfortable—painful even. The human brain is programmed to make this so. Likewise is it programmed for re-wiring when the right stimulus comes along, like a shift in conversation from telling to asking. May seem trivial, “ask don’t tell,” and yet it can be the key to unlocking breakthrough thinking – not just as a spontaneous spark, but more like an enduring flame, making innovation a cultural norm.

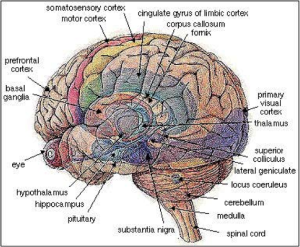

First things first: let’s see how we’re wired.

INNOVATION ON THE BRAIN

The basal ganglia serves as our auto-pilot, the part of the brain that operates around routine and habit. The prefrontal cortex, on the other hand, is our working memory, where new information or ideas are compared to old and where learning and insights are generated. Any changes to our hard-wired habits require much effort, attention and intention, putting the prefrontal cortex to work.

In addition to identifying “new” our brain is programmed to detect errors, the difference between expectation and actuality. When such a difference occurs, neural firing goes off in the brain in the orbital frontal cortex, which is in close vicinity to our fear circuitry, or amygdala. When activated, energy is drawn away from the prefrontal region, pushing people to act impulsively; animal instincts take over (fight or flight). When there’s a change to routine, a message in the brain is received to say that something is not right, overpowering our rational thought and, more significantly, our capacity for higher thinking. It takes a very strong will to push pass this mental activity to think differently and innovatively.

But wait—there’s hope.

FOCUS! THE POWER OF ATTENTION FOR HARDWIRING INNOVATION

Focus, that is, paying attention to a mental experience (thought, insight, image), is a powerful means for keeping our circuitry open. Over time, these circuits can become physical changes in the brain’s structure as a function of where an individual puts his/her attention. People who practice something new everyday literally think differently and over time become wired differently physiologically—hence why personnel from accounting, legal, marketing, human resources, R&D, etc. see the world differently from one another.

What we focus on is driven by expectation. David Cooperrider illustrated this in his “Positive Image, Positive Action” work. Human beings are like living video cameras, always anticipating the next scene before it occurs. And this expectation shapes our reality; what we look for, we find and what we pay attention to, grows. The more positive the image generated, the more positive the action that will follow. The opposite is also true.

What we focus on is driven by expectation. David Cooperrider illustrated this in his “Positive Image, Positive Action” work. Human beings are like living video cameras, always anticipating the next scene before it occurs. And this expectation shapes our reality; what we look for, we find and what we pay attention to, grows. The more positive the image generated, the more positive the action that will follow. The opposite is also true.

There has been much research in medicine to back this anticipatory reality concept, from positive imagery to placebo. Simply put: one’s mere expectation of pain relief can activate pain relief circuits in our brain so we experience what we expect to experience: pain relief. Norman Cousins, faculty at UCLA School of Medicine, used himself as a living laboratory in describing how his anticipatory reality enabled him to overcome a life-threatening illness: “Hope, faith, love, will to live, cheerfulness, humor, creativity, playfulness, confidence, great expectations—all of these, I believe, had therapeutic value.”

Cousins went on to argue that placebo validates positive imagery as a means to “awaken the body of its own healing powers.” Further research on placebo has shown that the response in the patient increases when supplemented by a positive expectation of the physician – that there is an interpersonal element to the positive image, positive action relationship.

This expectation is like a mental map, which can only be changed during moments of insight. A new set of connections are made, provoked in ways that change our attitude and expectation quickly and dramatically. Sometimes referred to as a paradigm shift, these moments of insight literally strengthen the brain’s capacity to overcome its own resistance to change. The more deliberate, repeat attention that is given to these insights, the greater the brain’s capacity to generate new connections. In other words, the more we strengthen our brain’s capacity for insight, the greater our chances of shifting mental maps and building capacity for innovative thinking.

ASK, DON’T TELL: INQUIRY FOR INNOVATIVE THINKING

“It’s not the answer that enlightens, but the question.” – Descouvertes

When people are asked questions that provoke new thinking and insight, the brain releases a rush of neurotransmitters that act much like adrenaline. This affords people the opportunity and responsibility of generating and owning their solution, a dramatically different process and outcome from being told (or persuaded on) what to do.

This positive rush of energy counters the amygdala’s impulsive fear circuitry. Further, it shapes the pathways of the brain to facilitate still more self-inspired insight (vs. advice-giving direction).

Through Appreciative Inquiry (AI) we ask questions that call for stories – reminding us what we value and want to see increased – as well as images of what can be – aspirations, outcomes and results. More significantly, we elicit focus and attention that otherwise might not be given, reinforcing insights around what has worked well. Complex connections are generated anew, creating new mental maps that, over time, can become hardwired circuits for making “out-of-the-box” thinking a cultural norm.

Better still, with an unconditional focus on the positive and what’s possible, inspiration becomes an almost inevitable result, which, consistent with Barbara Fredrickson’s “broaden and build” theory, broadens our thought-action repertoires. The more joy we have in our lives at home/at work, the greater our capacities to play and innovate. Fredrickson’s theory attributes positive emotions [made possible by positively biased inquiry] to our broadened attention span, through which we access greater strengths. Like an immune system, this fosters greater coping mechanisms that accumulate over time. The more hope, joy, and inspiration we experience in the workplace, the better we handle stress, and the more open we remain to seizing innovation.

GET TO WORK! EMBEDDING INNOVATION

We are biologically programmed to feel uncomfortable—and therefore to resist—when confronted with change. It’s in our survival instincts. But this is not to say we cannot overcome such programming and create circuitry anew—mental maps that, with practice, literally wire the brain’s capacity to generate breakthrough thinking and insight.

Widespread innovative thinking doesn’t happen by accident. Rewiring takes practice, deliberate attention and focus in a manner that shifts gears, provoking rapid moments of insight. The act of inquiry, particularly positively biased questions that tap into high point stories and experiences, enlighten us from the inside-out, shifting our mental maps in ways that didactic instruction (telling) cannot. Best part: questions broaden our thought-action repertoire, building capacity for breakthrough thinking and inspired action, “all-aboard ownership” to see ideas through.

So yes, our questions are fateful.

- FOCUS – direct attention to what you do want (not what you don’t)

- ASK – don’t tell. Shift the conversation. Very simply: invite more storytelling around what works, even if you have to stretch to look at exemplars elsewhere.

- RINSE & REPEAT – be deliberate and practice practice practice. You’ll be wired for innovation in no time.

Sources:

Cooperrider, D. (1999.) “Positive Image, Positive Action: The Affirmative Basis of Organizing.” Cleveland, OH; Case Western Reserve University.

Fredrickson, B. (1998.) “What Good Are Positive Emotions?” Review of General Psychology (vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 300-319); Educational Publishing Foundation 1089-2680/98.

Rock, D. and Schwartz, J. “The Neuroscience of Leadership.” Strategy + Business, Issue 43, Reprint No. 06207

Srivastva, S. and Cooperrider, D. (1999.) Appreciative Management and Leadership, Rev. Euclid, OH; Lakeshore Communications: 91-125.

Waldman, D.; Balthazard, P.A.; and Peterson, S.J.. (Feb. 2011.) “Leadership and Neuroscience: Can we revolutionize the way that inspirational leaders are identified and developed?” Academy of Management Perspectives, pp. 60-72.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!